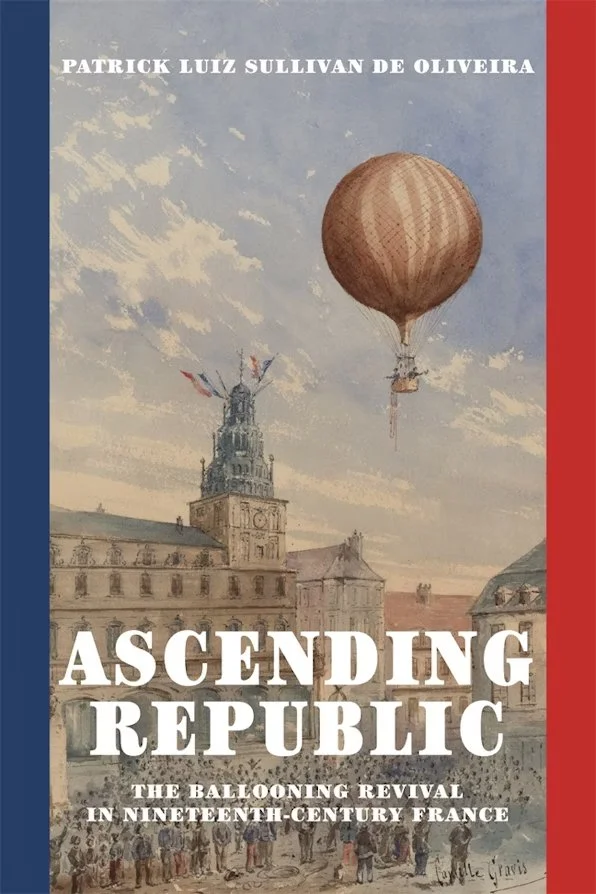

Why and how the French made the balloon into one of the quintessential symbols of late nineteenth-century modernity, and how the balloon's reinvention shaped the airplane's assimilation in the early years of aviation.

On August 27, 1783, a large crowd gathered in Paris to watch the first ascent of a hydrogen balloon. Despite the initial feverish enthusiasm, by the mid-nineteenth century the balloon remained relatively unchanged and was no longer seen as the harbinger of a new era. Yet that all changed in the last third of the century, when following the traumatic Franco-Prussian War defeat, the balloon reemerged to become the modern artifact that captured the attention of many. Through this process, the balloon became an important symbol of the fledgling Third Republic, and France established itself as the world leader in flight. In Ascending Republic, Patrick Luiz Sullivan De Oliveira tells for the first time the story of this surprising revival.

Through extensive research in the press and archives in France, the United States, and Brazil, De Oliveira argues that French civil society cultivated popular enthusiasm for flight (what historians call “airmindedness”) decades before the advent of the airplane. Champions of French ballooning made the case that if the British Royal Navy controlled the seas and the Imperial German Army dominated the continent, then France needed to take ownership of the skies. The French appropriated this newly imagined geopolitical space through a variety of practices, from republican savants who studied the atmosphere at high altitudes to aristocrats who organized transcontinental long-distance competitions. All of this made Paris into the global capital of a thriving aeronautical culture that incorporated seemingly contradictory visions of sacrificial patriotism, aristocratic modernity, colonial anxiety, and technological cosmopolitanism.

PRAISE

Based on novel research across three continents, Ascending Republic reveals the unexpected ways that the (re)discovery of ballooning in the Third Republic shaped French, European, and global history. History of technology of the highest order!

Andrew Denning, Associate Professor of History, University of Kansas; author of Automotive Empire: How Cars and Roads Fueled European Colonialism in Africa

Patrick De Oliveira masterfully chronicles the role that flight played in the life of the Third French Republic. Far and away the most successful of books exploring the roots of military aviation among European nations.

Tom D. Crouch, Curator Emeritus, Smithsonian Institution

In De Oliveira’s fascinating book, blimps are far from a blip—they are products and ciphers of an overlooked ‘airmindedness’ that offers a genuinely novel vantage on the politics and society of the belle époque.

Alexia Yates, Chair of Nineteenth-Century European History, European University Institute, and author of Selling Paris: Property and Commercial Culture in the Fin-de-siècle Capital